I’m going to share with you a journey I’ve been a part of since 22nd July 2009. A journey of tragedy, a journey into the realm of what was once science fiction but most importantly a journey of hope. I feel truly privileged to have been part of an incredible team of clinicians and scientists that worked tirelessly around the clock to help save a brave little boy from an uncertain fate and blessed to have had loyal family and friends provide strength and inspiration in troubled times. This little boy also happens to be my son – Massimo or as we like to call him Mo.

This journey really began in Paris almost ten years ago. My wife and I had just enjoyed six fantastic weeks in Europe on our honeymoon and we were now on our way home. We were trundling towards a Metro station with our wheelie bags of shopping to on the way to Charles De Gaulle. It was an unusually crisp winter’s morning and snowflakes started falling just as we descended into the Cluny Metro station in the heart of the Latin Quarter. An hour later we emerged in the departures hall of Charles De Gaulle. If you think this airport is chaotic on a good day you should see it when it’s blanketed with a dusting of snow – it is utter mayhem. We’d used all of our frequent flyer points to upgrade our tickets to business class on every sector except this one which was unfortunately overbooked. Despite trying our well-rehearsed “just married” routine at check-in it didn’t help bump us forward a few rows. Instead we were offered the front row of economy and complimentary lounge passes.

We sat in the lounge overlooking the snow covered vista of Paris and toasted farewell before being called to board our flight. When we eventually pushed back and took our place in the queue those quaint snowflakes had turned into quite a blizzard. There must have been a couple of inches of snow sitting on the wings by the time we neared the runway. Being an aviation enthusiast and avid Air Crash Investigation viewer the snow didn’t look quite so quaint any more. We turned onto the runway ready for take-off and paused a moment before the engines dropped to idle. The Captain’s voice came over the PA to announce some bad news – the airport had just been closed and he had been instructed to return to our gate and await further instruction. The delay was likely to be hours as we’d need to wait for the cold front to pass and then have the aircraft de-iced.

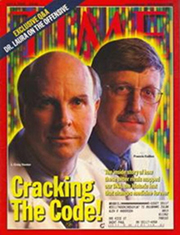

In order to not lose our departure slot the Captain decided we were going to stay on board the aircraft. As the hours rolled on we began to realise the advantages and disadvantages of our prized seats. Sure, the extra leg room was great but it was quite agonising to watch those in the next cabin washing down what seemed to be an endless supply of canapés with champagne while we ate mixed nuts. It did however afford us the luxury of being able to reach forward and pilfer a few magazines when the cabin crew weren’t looking. One of these magazines must have been kicking around the cabin for a couple of years and is almost certainly the reason I am standing here today. It was a well-read issue of Time Magazine with a picture of two men in lab coats on the cover. It was titled “Cracking the Code – The inside story of how these bitter rivals mapped our DNA, the historic feat that changes medicine forever”. The two men were Craig Venter and Francis Collins and the article described their race to sequence the first human genome. It was a fascinating read and one that planted the seed for my vague interest in genetics for years to come. Little did I know that six years later I would look back on this day and realise its significance.

At 9:15pm on the 22nd of July 2008 Massimo joined our world. The first four weeks were pretty much the norm – feed, sleep, poop, change nappy. I preferred to stay in the feed and sleep space but on occasion I was on change nappy duty too. On one of those rare occasions I noticed a small skin tag just above Massimo’s bottom and became mildly concerned. We eventually visited our local general practitioner who suggested Massimo have an ultrasound just to be sure. It turned out Massimo had Spina Bifida Occulta. One of his sacral vertebrae hadn’t closed and he had an associated tethered spinal cord and solitary left kidney. We were immediately sent to the RCH where Massimo underwent a brain and spine MRI to check for further involvement. At the time it all seemed incredibly serious but in hindsight there was really nothing to worry about – 1 in 750 males have a solitary kidney and up to 10% of the population has Spina Bifida Occulta. In most instances people go through life not knowing they have either. On the advice of his neurosurgeon we would just monitor Massimo for the next eleven months before making any decisions about surgery to untether his spinal cord. It was only the low lying conus of his spinal cord that was of concern as it could cause issues with bladder stability. With only one kidney this was potentially serious hence for the next 11 months we were closely watching Massimo for any tell-tale signs.

Massimo had a great first year hitting all the key milestones on or ahead of “schedule”. We’d had a couple of paranoid false alarms early on where we felt he was starting to tip toe but we were assured there was nothing to worry about. I had left the safety of the corporate world behind two years earlier to start my own business Eyre BioBotanics, a range of men’s skin care, and was finally about to reap the rewards of all the hard work. I’d just secured ideal placement in the United States and one of the products had been nominated for a Men’s Health Magazine Grooming Award – things were only going to grow from here. In May we enjoyed a well-deserved break, our first family holiday to Fiji. After a cautious start Massimo soon fell in love with the water and we struggled to pull him out of the pool at the end of day without alerting the whole resort and neighbouring islands! We had a great time and returned to Melbourne ready for the big year.

Massimo had a great first year hitting all the key milestones on or ahead of “schedule”. We’d had a couple of paranoid false alarms early on where we felt he was starting to tip toe but we were assured there was nothing to worry about. I had left the safety of the corporate world behind two years earlier to start my own business Eyre BioBotanics, a range of men’s skin care, and was finally about to reap the rewards of all the hard work. I’d just secured ideal placement in the United States and one of the products had been nominated for a Men’s Health Magazine Grooming Award – things were only going to grow from here. In May we enjoyed a well-deserved break, our first family holiday to Fiji. After a cautious start Massimo soon fell in love with the water and we struggled to pull him out of the pool at the end of day without alerting the whole resort and neighbouring islands! We had a great time and returned to Melbourne ready for the big year.

Soon after our return we started to observe some concerning signs of regression. Massimo was struggling to pull to stand and was getting very frustrated. His legs and particularly his ankles were stiff. He started having trouble with balance and kept thrusting his head back. Something didn’t seem right but all his bladder function tests returned normal and his follow-up spine MRI in mid-July didn’t ring alarm bells. He enjoyed his first birthday at home with family but we all sensed he wasn’t himself. The next day we visited his Physio at the RCH and she immediately realised something wasn’t right. She paged his neurosurgeon and by now the MRI had been formally reported noting a possible abnormality in the region of his thoracic spine. We were ushered to emergency where we were met by his neurosurgeon and she suggested it was possible transverse myelitis and ordered a brain and spine MRI. There was no sense of danger or urgency and the matter seemed well in hand. Massimo was transferred into the neuroscience ward as he needed to fast for several hours before the GA. At around 11pm we were called down to imaging – Massimo was taken into the MRI room and we were lead into the waiting room.

I remember that evening clearly. I remember starting to get concerned after an hour as the procedure should have taken only 40 minutes. I remember watching every stroke of Lance Armstrong completing the Annecy time-trial on his Livestrong bike in the Tour de France. I remember counting those long minutes as we waited two hours for the MRI to be completed. Finally, at 1:15am the neurosurgery registrar entered the waiting room and said we needed to talk. He asked a series of odd questions mainly directed at my wife about her diet, if she had any issues with B12 metabolism and if we were related but gave away little before leaving the room and saying Massimo was in recovery.

This was our Apollo 13 moment. The cryo-tanks had just exploded and the master alarm lights were flashing. Although uncertain of exactly what was going on we knew we’d just lost our son. There were no tears just silence. When we saw the sombre faces of the medical staff in recovery it confirmed our worst fears. Needless to say we didn’t sleep a great deal that night.

This was our Apollo 13 moment. The cryo-tanks had just exploded and the master alarm lights were flashing. Although uncertain of exactly what was going on we knew we’d just lost our son. There were no tears just silence. When we saw the sombre faces of the medical staff in recovery it confirmed our worst fears. Needless to say we didn’t sleep a great deal that night.

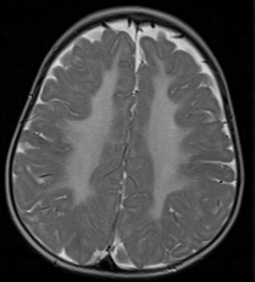

Early the following morning Massimo was handed over from neurosurgery to neurology. We met Massimo’s neurologist and were given our first look at his brain MR images. A new language entered our vernacular – myelin, white matter, T1, T2, hypo-intense and hyper-intense signals but the most frightening word we were to hear was Leukodystrophy – literally meaning “lack of white growth”. Analogies of electrical wiring were used to describe the condition where the insulation surrounding his nerves was breaking down and signals couldn’t effectively travel down the pathways. A barrage of tests was ordered and we were told we had to be patient but at no stage did I think we wouldn’t have an answer within hours or at worst days. Massimo was discharged and we returned home inconsolable. Needless to say Doctor Google was in overdrive and what we were reading wasn’t good. Leukodystrophy was a rare neurodegenerative disorder that would rob affected individuals of their sight and eventually all senses. The prognosis for infant onset was particularly poor with a life expectancy in months or at best only several years. There was no treatment, there was no cure and intervention was purely supportive of symptoms.

In the weeks that followed every test frustratingly returned back normal. When we saw Massimo’s neurologist and I was putting anything and everything on the table in desperation – stem cells, gene therapies you name it. Unfortunately his answers were always no. In the end I broke down and said “there really is no hope is there”. I knew what the answer would be but he thought about it a moment and responded “never let go of hope – there is always hope”. I am sure it must be as difficult for a doctor to tell parents this as it is for parents to hear it because everyone knows what it really means. He tried to be positive and told us that we’d ruled out some really nasty conditions and this was good news. We were narrowing down the remaining possibilities and genetic tests for PMD and a specific variant of Hypomyelination (FAM126A) were ordered from O/S laboratories in the United States and Italy. We were told the time frames for these tests were many months and that we needed to be patient. We were also told to be prepared that up to 50% of these white matter disorders remained undiagnosed.

Meanwhile Massimo’s condition continued to deteriorate rapidly. He started to choke on food and water, lost all his vocabulary and could no longer crawl or sit. He looked sick and weak and I’m sure he knew something terrible was happening because he looked really scared. Although, it was never explicitly stated I don’t think anyone expected him to see much of 2010 including me. Things were happening too fast.

Never had I found myself in such a hopeless situation. In my mind’s eye I thought this is what it must feel like to be on a plane about to crash. At some point an instinct within accepts the end is near, you close your eyes and it’s all over in a flash. In this case we couldn’t see the end – was it a weeks, months, years or decades? Until you are faced with these circumstances it is difficult to comprehend the permutations of life that go through your mind. You start planning for every possible future outcome but can only live for the day. It was tough, very tough and for me it was impossible to accept. The only way I could cope was to throw everything behind a diagnosis. I had to know why this was happening and if we were to one day access or develop a treatment we needed a diagnosis. I simply wasn’t going to give up until I had one.

Three months passed since 24/7 (our 9/11) and we were still waiting on results from Italy. It was at this point I raised whole genome sequencing. After all I’d read about it years ago and surely this historic feat that would change medicine forever was now a reality. The price had come down to a not insignificant $50k per genome and the analysis part all seemed pretty straight forward in theory. You get the affected child and parental genomes, align them with the latest version of the human genome baseline and run some complex algorithms on your local IBM Blue Gene and out pops the answer. How hard could it be? I soon found out this wasn’t being done on a regular basis and analysing the data with only one affected child wasn’t going to be easy. Not impossible, but not easy. Instead we were going to have to wait for another MRI in three months and hope that any signal changes may focus our search. The final outstanding test returned back negative just before Christmas. It was a difficult time as twelve months earlier every special event was our first as a family and now we were feeling they were our last.

Three months passed since 24/7 (our 9/11) and we were still waiting on results from Italy. It was at this point I raised whole genome sequencing. After all I’d read about it years ago and surely this historic feat that would change medicine forever was now a reality. The price had come down to a not insignificant $50k per genome and the analysis part all seemed pretty straight forward in theory. You get the affected child and parental genomes, align them with the latest version of the human genome baseline and run some complex algorithms on your local IBM Blue Gene and out pops the answer. How hard could it be? I soon found out this wasn’t being done on a regular basis and analysing the data with only one affected child wasn’t going to be easy. Not impossible, but not easy. Instead we were going to have to wait for another MRI in three months and hope that any signal changes may focus our search. The final outstanding test returned back negative just before Christmas. It was a difficult time as twelve months earlier every special event was our first as a family and now we were feeling they were our last.

When the day arrived for Massimo’s long awaited next MRI in January it showed some subtle changes. We were fortunate that Massimo’s neurologist had a direct line to a Professor in Holland widely regarded as the world’s expert in in white matter disorders. She suggested Massimo may have early stage Vanishing White Matter (VWM) disease although his clinical presentation didn’t fit with the disease. Consequently none of the limited public funding was made available and private health insurance didn’t cover genetic testing. At this point we were effectively on our own and if we were to fund the VWM tests privately the cost was around $10k – coincidentally the new price of the Illumina’s WGS service. I thought the MRI approach seemed appropriate to broadly categorise known variants early on but it was now blunt instrument and we were relying on changes over six to twelve month intervals. We decided to proceed with WGS. At the very least the data would be available to check for other diseases at any point in the future and local genetic services agreed to perform the analysis to rule out the five genes responsible for VWM.

Over the next six months Massimo’s condition appeared to stabilise and he actually regained some lost skills. This was strange as the typical course of a Leukodystrophy is relentless. He was also exhibiting a growing disparity in the spasticity between his upper and lower limbs. This was a unique feature in his presentation which baffled everyone. Perhaps the unusual combination of his tethered cord and the high signal were acting together – no one really knew.

Months earlier I had setup a series of Google Alerts on various search strings focusing on this nuance. In early August I received an email with several alerts referring to a disorder known as Leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord abnormalities and elevated lactate (LBSL). The author of the paper was none other than the Professor from Holland. It wasn’t a perfect fit but it certainly was the best fit to date. Massimo had another MRI in mid-August and sure enough the Professor suggested LBSL was a possibility. The genome data was now available but unfortunately DARS2 turned out to be a false alarm, along with the five genes for VWM.

2010 was drawing to a close and sitting on my desk was a unassuming black USB HDD labelled PG0000045 – I assume the nomenclature was short for Personal Genome #45. It contained the answer we were looking for but it may as well have been the black obelisk from 2001: Space Odyssey as I certainly felt like one of the apes staring at it in bewilderment. We’d reached a dead end. I was convinced Massimo had an unknown variant and we needed to go wider rather than focus on known conditions. Moreover, the clock was ticking and I wasn’t prepared to wait another twelve months. I arranged to have the data analysed by the National Centre for Genomic Research (NCGR) in the US. The genome would be run through their pipeline and what would come out the other end was anyone’s guess. We hoped it wasn’t going to be a staggering number but unfortunately it was 11,500 SNPs – a number too great to work with.

2010 was drawing to a close and sitting on my desk was a unassuming black USB HDD labelled PG0000045 – I assume the nomenclature was short for Personal Genome #45. It contained the answer we were looking for but it may as well have been the black obelisk from 2001: Space Odyssey as I certainly felt like one of the apes staring at it in bewilderment. We’d reached a dead end. I was convinced Massimo had an unknown variant and we needed to go wider rather than focus on known conditions. Moreover, the clock was ticking and I wasn’t prepared to wait another twelve months. I arranged to have the data analysed by the National Centre for Genomic Research (NCGR) in the US. The genome would be run through their pipeline and what would come out the other end was anyone’s guess. We hoped it wasn’t going to be a staggering number but unfortunately it was 11,500 SNPs – a number too great to work with.

The next logical step was to have our parental genomes sequenced and we hoped that running the trio would reduce the noise. Again, no one could guide us on what would come out the other end because it hadn’t been performed locally and only a handful of times internationally. The next challenge was to find someone able to perform this trio analysis as local genetic health services didn’t have the expertise. Our search for a diagnosis has now become a research project but we didn’t have researchers.

Over the past three years we’d built a close working relationship with our general practitioner. I would constantly go on about needing a bioinformatics guru and at one point suggested I would do it myself after having read Genetics for Dummies and Bioinformatics for Dummies!

I was thinking of all sorts of options including setting up an X-Prize and notifying institutions around the world. Our general practitioner was also keen writer and had just returned from a writing conference in the US. As luck would have it one of her fellow attendees was married to a post-doctoral fellow in bioinformatics right here in Australia. We were introduced via email where I shared the history of our efforts and thoughts on moving forward with a trio. He agreed the strategy was sound and before long went on suggest he may be able to help us a little more. He was keen to perform the analysis himself and had shared our story with the folk at Illumina who offered to provide reagents in-kind for the sequencing. That person is Dr Ryan Taft. Over the next nine months everything slowly fell into place and he completed the trio analysis in early December. Incredibly he narrowed down our 11,500 SNPs to a compound heterozygous mutation in the DARS gene and we hoped this was finally the answer to all our efforts.

With a potential strong candidate next we needed to validate the finding which is easier said than done. Ideally we needed to find a cohort of similar affected children to identify the same compound heterozygous mutation. Fortunately, two years prior Massimo had been enrolled in a research project being run out of the Children’s National Medical Centre in Washington DC for unclassified white matter disorders. The objective of the research project was to build a bioregistry of children and parent DNA and then to one day perform a similar exercise to what Dr Taft had just completed on clusters of similar patients. Upon sharing the findings with the research leader four family trios and a family of five with two affected children were identified with similar imaging and clinical presentation. All of these patients underwent whole genome sequencing for parallel analysis. The family of five with two affected children were identified as having mutations in the DARS gene validating the preliminary finding. The finding was further validated with seven additional patients identified from Europe and the Far East with mutations in the DARS gene. We had successfully diagnosed a previously unclassified white matter disorder and provided the proof of concept for familial trio genome analysis as an effective clinical diagnostic tool for novel genetic disorders.

Beyond Massimo, I hope our collective efforts will pave the way to diagnose many other children and just maybe treat their rare genetic disorders. What started as a skunk works project has grown into an international multi-institute collaboration linking the right people from the various disciplines from diagnosis through to treatment. What took years for us may soon take weeks, days or eventually hours allowing early intervention and treatment. Above all, looking past the incredible science and technology it offers hope to the many families in the terrible situation that we were once in ourselves.

Being an aerospace enthusiast I turned to one of my favourite inspirational quotes when our lives changed forever. President Kennedy’s ambitious challenge to the American people of “committing to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” At the time such an ambitious goal was science fiction. The challenge to diagnose Massimo and to develop a therapy was in many was just as ambitious. In 2009 using trio whole genome sequencing was at the bleeding edge of genetic science and just like going to the Moon forty years earlier it bordered on science fiction. The Apollo program may have been politically motivated, to some degree, but it united a nation into achieving a common goal and the results were nothing short of spectacular. Massimo needed his own Apollo program and it needed to be relevant and inspiring to this generation of researchers. We named our program Mission Massimo and its motto “Scientia Est Potentia” (Knowledge Is Power). Because the knowledge of a diagnosis would hopefully one day give us the power to develop a treatment.

Achieving a diagnosis was only the first step of our journey. Our next challenge is to develop a therapy. We are already working on viral delivery systems to transport a corrected copy of the DARS gene into the central nervous system halting progression of the condition and allowing myelin to form. Ultimately, we hope to introduce CRISPR corrected induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) derived from skin fibroblasts to repair the damage done. This is still science fiction today but as history has shown us with the right commitment we can make it tomorrow’s science fact.

Our experience compelled us to establish the Mission Massimo Foundation to raise funds for genomic diagnostics and gene therapy and stem cell research. It’s important to reiterate that 50% of Leukodystrophies remain genetically undiagnosed and therefore research into therapies for these novel disorders is not possible. If we can reduce the number undiagnosed Leukodystrophies to <10% before 2020 and develop a common suite delivery platforms it will be a profound breakthrough in the treatment of this debilitating condition.

Sadly, Massimo passed away peacefully in his sleep in the early hours of Friday 15th December 2017. Massimo went to bed happy and smiling, as he always did, but in the morning he was no longer with us. We believe Massimo’s death was most likely a primary cardiac arrest caused by autonomic neurological dysfunction in the brainstem. Massimo’s condition, Hypomyelination with Brainstem and Spinal cord involvement and Leg spasticity (HBSL), as the name suggests, severely affects the myelin of the brainstem with almost no progression from birth. The brainstem is involved in the control of respiration and cardiac function. Massimo’s heart likely went into an uncontrolled arrhythmia and stopped whilst he was fast asleep.

Massimo was the happiest and healthiest he had been in the week preceding and we can take some solace in knowing that he never had to endure the later stages of this terrible condition. This knowledge doesn’t bring him back but provides some solace and over time we will grow to appreciate the quality times we had together even more.

Massimo and his mission will always be remembered as an enduring example of courage, persistence, love and teamwork. Massimo showed us all what the very best of humanity can achieve working together to achieve a common goal.

Thank you for reading our story and please take a moment to listen to the speech that inspired us to reach for the stars. We hope you can join our mission to end childhood leukodystrophies.

Stephen Damiani

Chairman | Mission Massimo Foundation